In Japan, day after day, service and assistance robots make up the task force that meets human needs and overcomes bottlenecks. Their purpose is to give ageing society professional and personal assistance. ERICA helps at the reception desk, while Lovot combats loneliness. Increasingly human-looking robots are also welcome elsewhere.

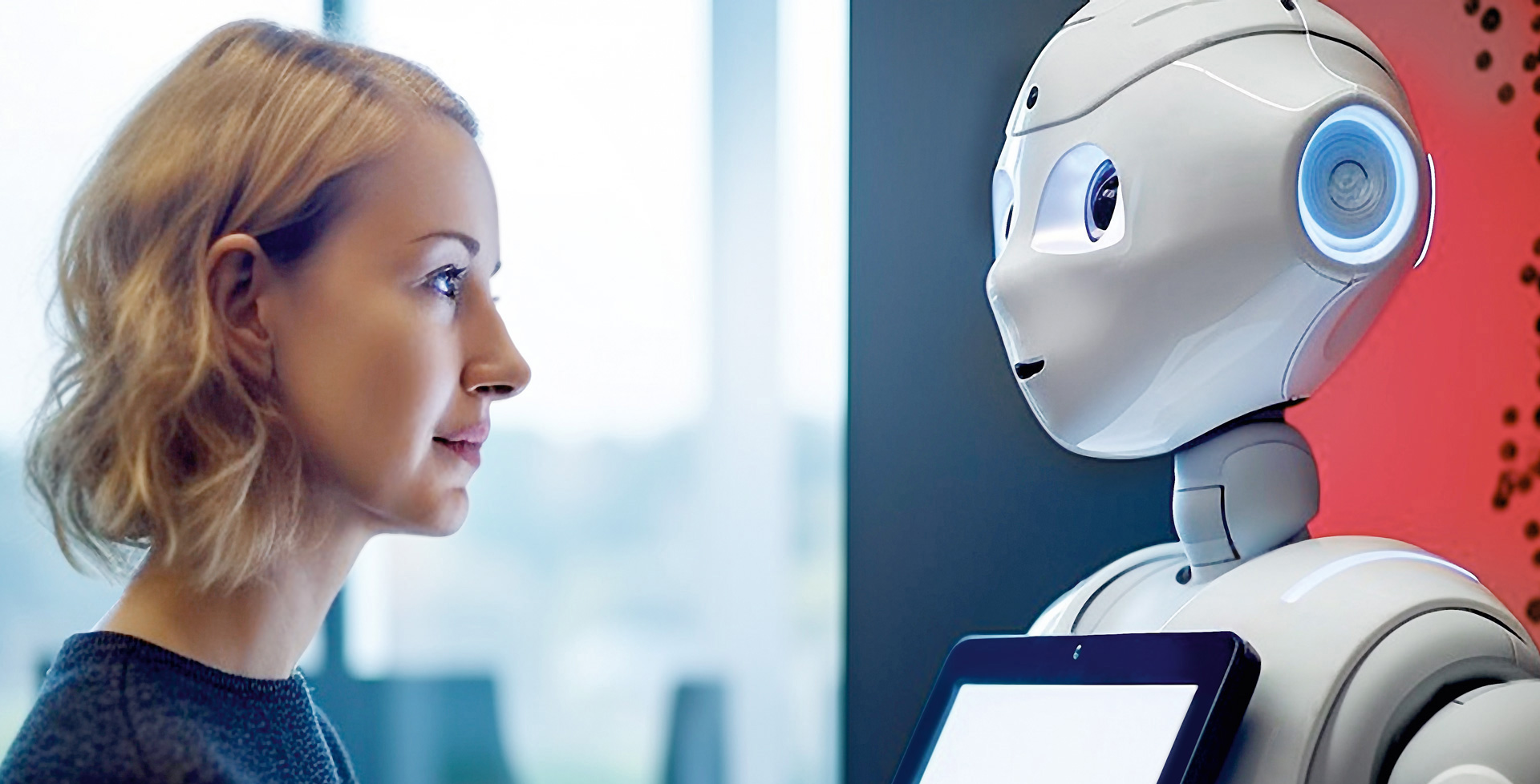

Pepper, the humanoid robot, behaves impeccably in company as well as in the shop, listening, talking and even dancing.

The bakery employees have a lie-in while their collaborative robot or “cobot” workmates prepare baking trays for the oven and stock the appetising displays in the shop. A cobot, a baked goods presenter that keeps an eye on things with artificial intelligence, and a network-compatible oven that automatically loads and unloads, collectively ensure in the early hours that freshly baked products reach the breakfast table on time. Together they comprise the “Bakisto” team system consisting of a Japanese robot, the Bavarian-Swabian based BakeOff i and the Württemberg-Swabian Dibas blue2 with TrayMotion. Their human colleagues arrive later. And therefore with all the more enthusiasm. This is no longer an isolated case, for trade and commerce are making use of cobots because they are adaptable, do not require protective fences and are easy to program.

From a Japanese point of view, robots have a soul – like everything in nature. Why should anything around us be lifeless, or even dead, if it is even capable of moving us? That sounds appealing, especially if robots are expected to or have to replace humans. Robots-as-a-service take on important roles not only in manga comics when demographic change and the lack of skilled labour encourage the shedding of uncomfortable routines. “Would you like a coffee?” – The words of Pepper, the robot companion Pepper from Softbank, or rather from Aldebaran and the United Robotics Group, sound tempting as you walk through the IFA Berlin trade fair. The bug-eyed communications professional charmingly entices weary trade fair visitors to a smart technology stand. As is so often the case, the people he addresses cannot resist the friendly mechanical being, especially as he eagerly supplies information and gives directions. Pepper, this archetype of a humanoid service robot consisting of arms, a head, a touch screen and a mobile undercarriage, is also popular as a companion in retirement homes. The social robot reacts to emotions and gives attention. And he provides interactive entertainment with games and fitness instructions. Yet there’s room for improvement. Pepper can’t pour out coffee. Nor play chess or empty the dishwasher, skills that the next generation of assistance robots will gradually acquire for everyday life. Necessary for this are such technological advances as advanced language models, artificial intelligence (AI), sensitive sensor technology, gripper arms with multi-functional hands, and all-round camera systems. Best of all so-called “multimodally interleaved systems”, for which autonomous, reflexive behaviour as well as transfer services are commonplace in digital and changing environments.

From a Japanese point of view, robots have a soul – like everything in nature. Why should anything around us be lifeless, or even dead, if it is even capable of moving us? That sounds appealing, especially if robots are expected to or have to replace humans. Robots-as-a-service take on important roles not only in manga comics when demographic change and the lack of skilled labour encourage the shedding of uncomfortable routines. “Would you like a coffee?” – The words of Pepper, the robot companion Pepper from Softbank, or rather from Aldebaran and the United Robotics Group, sound tempting as you walk through the IFA Berlin trade fair. The bug-eyed communications professional charmingly entices weary trade fair visitors to a smart technology stand. As is so often the case, the people he addresses cannot resist the friendly mechanical being, especially as he eagerly supplies information and gives directions. Pepper, this archetype of a humanoid service robot consisting of arms, a head, a touch screen and a mobile undercarriage, is also popular as a companion in retirement homes. The social robot reacts to emotions and gives attention. And he provides interactive entertainment with games and fitness instructions. Yet there’s room for improvement. Pepper can’t pour out coffee. Nor play chess or empty the dishwasher, skills that the next generation of assistance robots will gradually acquire for everyday life. Necessary for this are such technological advances as advanced language models, artificial intelligence (AI), sensitive sensor technology, gripper arms with multi-functional hands, and all-round camera systems. Best of all so-called “multimodally interleaved systems”, for which autonomous, reflexive behaviour as well as transfer services are commonplace in digital and changing environments.

“You certainly have warm hands!” Anyone who strokes the purring BellaBot high-tech serving cat not only gets their order, but also a compliment. (© Joeri – stock.adobe.com)

Robots also make work and life easier outside of factories. As waiters in restaurants, for example, mobile service and transport robots provide assistance to humans. Servi is a courteous serving tray on wheels, the outcome of cooperation between the Softbank Robotics Group and Bear Robotics. The indoor robot serves customers, patrols and collects dishes. Outside the door in the Meguro district, the mini-mobile from ZMP, a Tokyo pioneer in robot design, is already in operation and, as a delivery robot, is making its contribution to the digital city. A pleasant smile, a friendly question as to whether the guest has had a good trip or a pleasant day, and even in the appropriate language: this kind of personal service is to be provided by android robots in so-called Henn-na Hotels in Japan. Receptionists, for example, who are modelled on humans, with silicone skin and a flutter of the eyelashes to simulate vitality. The Japanese “Henn na” means “forward-facing” or “changing” in English. One such highly automated overnight resort in Nagasaki has even made it into the Guinness Book of Records. At CES, Pollen Robotics presented their French robot Reachy, a creepily friendly open-source type with AI in its head and wheels on its legs that is capable of handing out keys at a hotel reception, for example. With their grasping hands, such sensitive companions are coming into closer contact with people in everyday life and are becoming useful in many areas.

(© Vershinin89 – shutterstock.com)

In the 1980s, Honda built the humanoid robot Asimo, a favourite of the Japanese and the country’s visitors, that even shook hands with former German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Since then, Asimo hasn’t just got older, but has continued to evolve. Meanwhile, the veteran robot can even play football, although it is radio-controlled. Differences even blur when choosing between partners from the machine room and the world’s sporting elite. Fans call tennis star Rafael Nadal a machine. The Korean training robot iVolve Pro whizzes across the court with similar precision. Equipped with artificial intelligence and computer vision, the ball machine from Curinginnos replaces a human opponent. The winner of the CES 2023 hits balls in rapid succession here, there and everywhere.

The work-life balance is becoming increasingly important. So are pragmatism, efficiency and smart solutions for problematical situations. Sleeping longer instead of setting off early and travelling long distances to an appointment is now possible. With telepresence robots, such as those from Double Robotics, anyone can virtually attend real meetings by switching to their stand-in via PC or smartphone. The seats of sick or immunocompromised pupils, students and lecturers are occupied by doubles with display heads equipped with loudspeakers, microphones and cameras. For logistics and warehouse work, the intelligent double travels through warehouses and offices instead of its human counterpart and checks the situation. In hospitals and old people’s homes, too, telerobots pop in to take the strain off human staff or enable otherwise prohibited on-site visits by connecting friends and relatives live on their displays.

In Europe, people prefer robots that don’t resemble them too much but are still intelligent.

Very special remote workers are the brainchild a creative research lab in Japan. By this we mean telephony that has become robotic, and about waxwork-like androids designed to blur the boundaries between humans and machines. As “telenoids and waxwork-like” created by the robotics engineer Hiroshi Ishiguro at Osaka University, these surrogates even record human movements and facial expressions live via a computer program, transmitting the human’s words via voice software. In the case of their creator, the humanoid android dummy looks roughly like its human original. Telenoids may even wear the human’s hair. A human being much in demand cannot replicate himself with such telepresence robots, because he controls them from a distance and they only embody him. In the variant as series-produced soft, hairless beings for ordinary folk, telenoids are not attempted clones in robot form, but simply a little humanised.

And then there is the Geminoid F, to enable it to act autonomously, cognitive scientists want to teach it needs – like smiling, for example, in order to be loved. The humanoid android ERICA is already autonomous within her reference space. The young woman works at reception desks, hotels, retirement homes or even at a research lab in Japan. In the science fiction film b, she landed a leading role in Hollywood. Humanoid androids like ERICA score points with human looks, reactions, shaking their heads or thoughtful responses to key words in conversation. This is initially enough to establish a kind of personal relationship between a robot and a human being.

“Give me a stroke!” The harp seal cub Paro responds to touch. (© Beru – shutterstock.com)

Robots can also be therapeutically effective. “Paro”, a baby harp seal, was designed in a Japanese developer’s workshop in the previous millennium. This personal medical robot has been on sale since 2004. The cute robot seal’s road to success has also taken it to German institutions. The furry animal that can be stroked and cuddled is said to have a positive effect on dementia patients with its life-like responses. Though resembling a sloth, Lovot follows his humans around, has big saucer eyes, a heart choc-a-bloc with AI and a cuddly suit. He is another brainchild of Kaname Hayashi, Pepper’s originator, who is now the head of the Japanese start-up Groove X.

Android receptionist at Hen-na hotel in Ginza (© Ned Snowman – stock.adobe.com)

In some places, the future has already arrived for the humanoid Aeo, a robotic assistant designed to make people happier and more productive in open, human environments. Aeolus Robotics aims to bring its intelligent robotic services from Japan to Europe and the US. This means that robots are already available for “pickup-navigate-deliver” or “monitor-decide-warn” applications. For example, in care homes for the elderly, in hotels, at airports, in restaurants and on security missions. Aeo is firstly strong enough to lift heavy loads, but also careful enough to delicately handle medicines or electronics with its two hands. One hand disinfects and delivers, while the second arm opens the door. Technologies such as navigation, deep learning, AI and vision help him do this.

“Let me carry that!” At theme parks, digitally equipped dinosaurs lend a hand and take the strain off hotel staff. (© Ned Snowman – stock.adobe.com)

Three questions to Professor Bruno Sicilian

In December 2006, Bill Gates wrote in Scientific American that we are at the “dawn of the age of robots” and that within about two decades we will have “a robot in every home”. We are fast approaching this scenario. In my opinion, the big challenge is to make robots as intuitive as possible so that they can be used by anyone, like commercial plug-and-play devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. Only then will we have personal robots as companions in our daily lives, at work, at home, at school, in hospitals, in agriculture and in virtually every human environment. Come that day, robots will live alongside humans and robotics will have become a pervasive and ubiquitous technology.

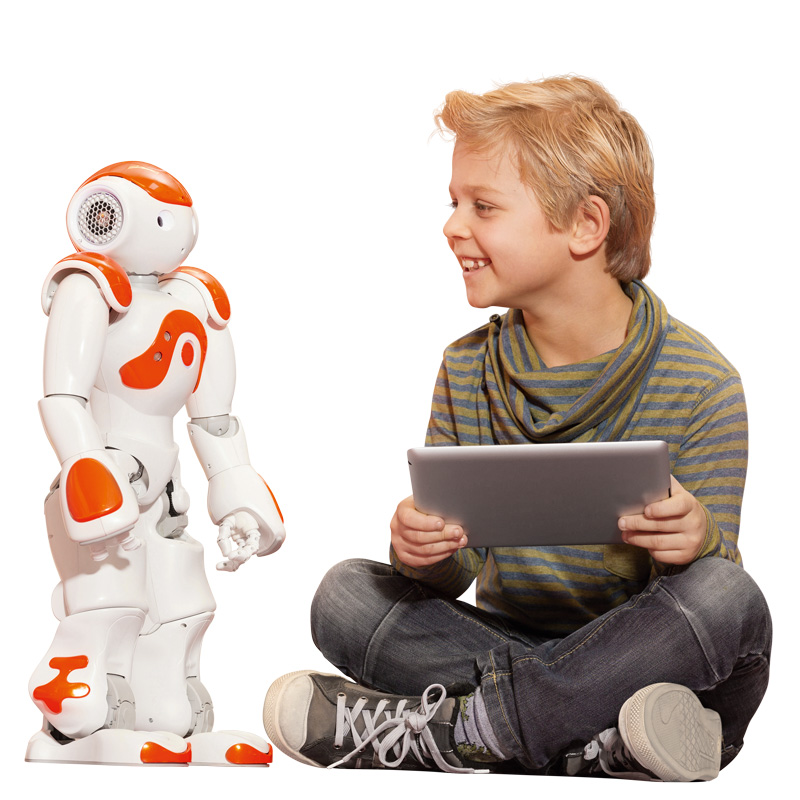

This is an important, ethical question. If you look at Japanese families, they have Pepper at home, a robot from the French company Aldebaran that was bought by the Japanese company Softbank. The robot is with their children and they can use it to keep an eye on them because it has a camera. Caregivers with limited cognitive or physical abilities might maltreat the children entrusted to their care. Babysitters might smoke or prepare food that is not fresh. If you have a machine that you trust, that you can rely on and that has programs designed by humans and has been programmed well, machines could certainly handle assistance tasks.

This is an important, ethical question. If you look at Japanese families, they have Pepper at home, a robot from the French company Aldebaran that was bought by the Japanese company Softbank. The robot is with their children and they can use it to keep an eye on them because it has a camera. Caregivers with limited cognitive or physical abilities might maltreat the children entrusted to their care. Babysitters might smoke or prepare food that is not fresh. If you have a machine that you trust, that you can rely on and that has programs designed by humans and has been programmed well, machines could certainly handle assistance tasks.

“Come here!” The cuddly robot Lovot moves towards the speaker, blinking. (© Hannari_eli – shutterstock.com)

In its interaction with autistic children, a robotic cuddly toy has proven to be much more dependable than a live animal. The therapist should program the robot to help the autistic child make progress – in the cognitive field, for example. You may one day come to the realisation that machine assistants are more reliable than human ones.

If you program your robot to be good to your children or to elderly people, it can help. I don’t believe in a world where robots will replace us. But there are dangerous, boring and fatiguing jobs in factories, in the home and in hospitals that could be done by robots. Exhausted nurses may make mistakes when dispensing medication. Robots can check the dispensing of medicines and do everything very accurately.

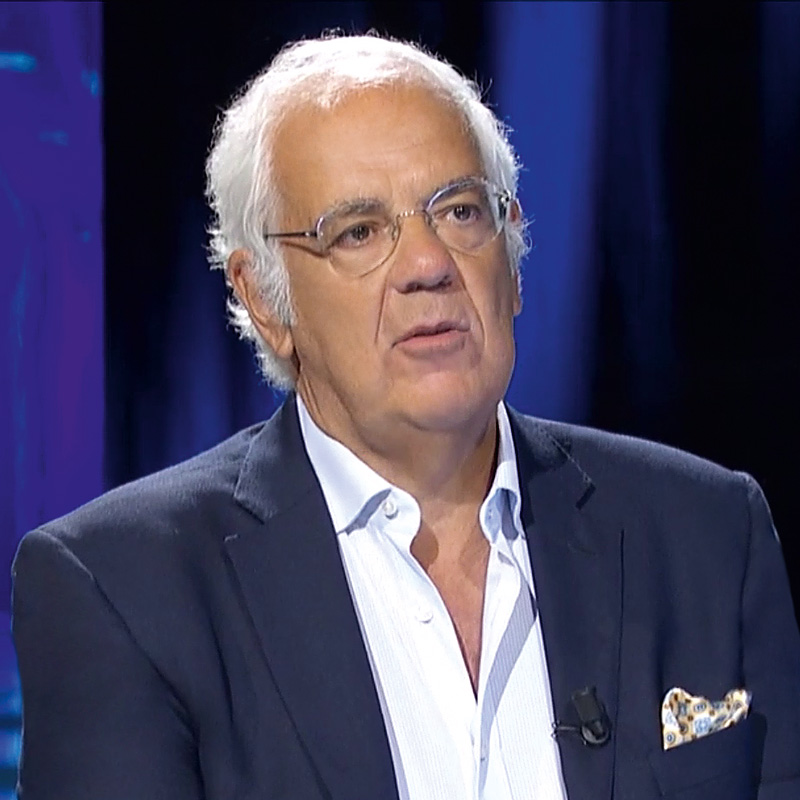

Professor Dr Bruno Siciliano, born in 1959, is Professor of Robotics and Coordinator of the PRISMA Lab at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology of the University of Naples Federico II. His research fields include force feedback control and visual robot control, cooperation between humans and robots, and flight and service robotics. He was director of ICAROS, the Interdepartmental Centre for Robotic Surgery, which seeks to create synergies between clinical and surgical practice and research into new technologies for computer- and robot-assisted surgery.

Professor Bruno Siciliano, Professor of Robotics and Coordinator of the PRISMA Lab at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology of the University of Naples Federico II.

Fields marked with a * are mandatory.

Mitsubishi Electric Europe B.V.

German Branch

Mitsubishi-Electric-Platz 1

D - 40882 Ratingen

Sales

Tel.: +49 (0)2102 / 486 - 6120

edm.sales@meg.mee.com

Service

Tel.: +49 (0)2102 / 486 - 7600

edm.hotline@meg.mee.com

Applications

Tel.: +49 (0)2102 / 486 - 7700

edm.applikation@meg.mee.com

Spareparts

Tel.: +49 (0)2102 / 486 - 7500

edm.parts@meg.mee.com